“Ambulatory archives of movie star womanhood”: Drag Queens in Andy Warhol’s Art

Drag queens – people who use dress and makeup to imitate and exaggerate female gender signifiers for entertainment – were of great fascination to Andy Warhol, who explored the figure through varying mediums, including the silkscreen, photography and performance.

This career-long interest was triggered in 1974 when Warhol received a commission from Italian art dealer Luciano Anselmino who asked him to produce a series of screen-print portraits of New York’s drag queens. The artist sent off Bob Colacello, editor of Interview magazine, to scout for prospective sitters. Most of the drag queens that made it into the body of work, titled Ladies and Gentlemen 135, were performers at the Gilded Grape club just off of Times Square. Colacello recalls that he would “ask them to pose for ‘a friend’ for $50 an hour. The next day, they’d appear at the Factory and Andy, whom we never introduced by name, would take their Polaroids.” Among those who came through the doors of Warhol’s iconic studio was Marsha P. Johnson, remembered today as one of the most famous drag queens in history and a renowned black trans activist who led the Stonewall uprising in 1969. However, due to the covert process of photographing the subjects many of the faces featured remained anonymous until reasonably recently. It was not until 2014 that a team of researchers worked to uncover their names and identities, although some remain unknown.

The $1m commission was the first major thematic group of works based on his use of Polaroid photographs, which had become Warhol’s primary modus operandi once he ceased using appropriated images out of fear of copyright infringement lawsuits. It also marked the beginning of a long-term fascination with the figure of the drag performer. Throughout his work, Warhol was preoccupied with the idea of surface, artifice and celebrity. So for Warhol, the drag queen, who employed clothing and heavy makeup to simulate the impression of hyper-femininity and create a fantasy of filmic glamour, was a remarkably well fitting subject for the artist to explore.

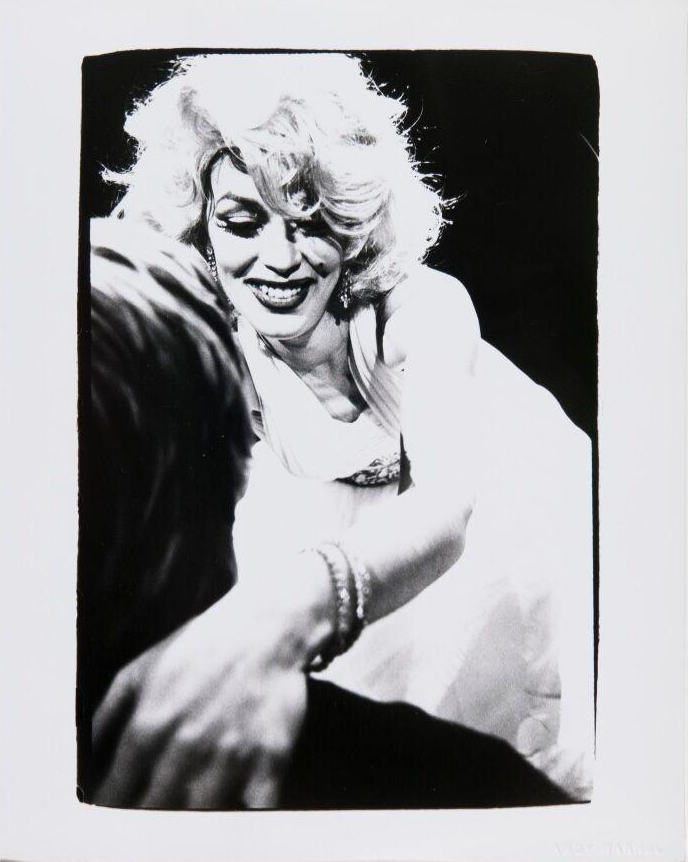

Drag Performer, 1981, was taken years after the Ladies and Gentlemen 135 series was wrapped up, proving that Warhol continued to frequent bars that showed drag performances in the years following. The drag queen in the photograph appears to be mid-performance as she stands elevated over an anonymous audience member who has their back to the camera. Her hand is placed seductively on the figure’s shoulder as she looks down on him, illuminated and radiant. The white halterneck dress cinched at the waist with a belt, the short, blonde wig, drawn-on mole and diamante jewels conjure the classic, golden-age glamour of America’s most iconic movie stars, Maralyn Monroe, which Warhol had already rendered in a series of screen prints throughout the 1960s. If it weren’t for the strands of dark hair spilling out of the wig’s hairline, she would indeed resemble an example of flawless femininity. For the artist, drag queens seemed to evoke a particular category of femininity that had become a thing of the past. Warhol once claimed that ”[drag] queens are ambulatory archives of movie star womanhood.” Elsewhere he said that drag queens are “living testimony to the way women used to want to be, the way some people still want them to be and the way some women still actually want to be.”

Compositionally the photograph dramatises the seduction and power of the drag performer. She looms over the male figure, who is pushed into the corner of the frame whilst she dominates the pictorial space. Her hand, which extends towards the camera and tightly grasps the shoulder of the male figure appears disproportionately large compared to the rest of her body, becoming symbolic for the rapture of beholding such a spectacle. The stage lights light up the drag performer’s blonde wig. In fact, her whole persona is electrifyingly as she forms a diagonal strip of bright exposure through the photograph that is offset by the jet black that flanks her.

In the same year that the photograph was taken, Warhol himself experimented with drag and took a series of self-portraits and videos in the early 1980s of himself wearing a wig and makeup. This sort of cross-dressing performance for the camera has a long precedence in western art, most famously done by Duchamp, who invented a female alter-ego named Rrose Sélavy. Warhol’s assistant Christopher Makos who helped with the drag self-portraits described the process as a “Dadaist experiment…The point was not drag itself but the altered image.”

Contact us to arrange a viewing of our Warhol photography exhibition.