Our Venice Biennale Highlights

Two weeks ago, the jet set of the contemporary art world continued their breakneck pace around this year’s circuit of must-see/must-be-seen-at-events with the preview of the 2019 Venice Biennale, titled “May You Live in Interesting Times”. It seems as though the whirlwind of Frieze New York is in the distant past.

The crowds were heavy during the preview with Artvisor’s team in attendance. That said, the buzz was that many collectors, particularly those from the US, have decided to come to Venice en route to Art Basel, which takes place in mid-June.

Now that we’ve had some days to catch our breath it’s time to share some of our insights, highlights and favourite exhibitions for those who are thinking of attending the Venice Biennale in the coming months.

Let’s talk about the format…

The curator of the main exhibition Ralph Rugoff, also director of the Hayward Gallery in London, has a reputation for creating exhibitions that feature diverse artists working in and around complex ideas. Going into the 58th Biennale, we anticipated a degree of provocation. Indeed, Rugoff has attempted to rock the boat, choosing to show many of the same artists in both the international pavilion of the Giardini and the Arsenale in equal measure.

The themes of disruption, norm-challenging and chaos were central to the design of the show, as well as the surrounding pavilions that were not in the aforementioned main/traditional areas of the Biennale. Ultimately, it was somewhat jolting to see very similar works by the same artists displayed in either context. We have usually anticipated seeing a totally different display moving from one of the main venues to the next. While seeing mainly living artists was refreshing, it was also the same artists we often see in London and at the global fairs we have visited so far… new discoveries were lacking.

Starting from the outside, here are some of the best shows we saw last week beyond the Giardini.

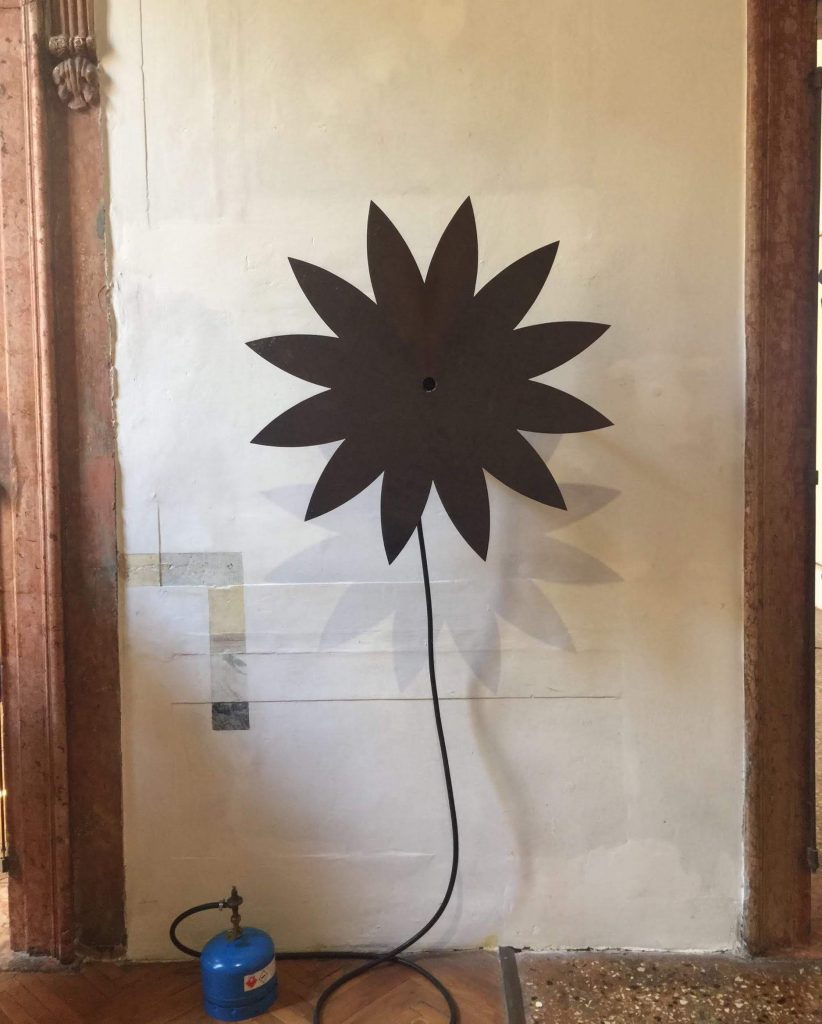

Jannis Kounellis @ Fondazione Prada – Title: ‘Jannis Kounellis’ , Location: Calle Corner, 2215, 30135 Venice

Being the first major retrospective since the artist’s death in 2017, this exhibition curated by Germano Celant, brings together 60 works from 1959 to 2015. It is, perhaps one of the most monumental Kounellis solo exhibitions that has ever been assembled. ‘Jannis Kounellis’ is an exceptional show.

To begin with, the architecture of the historic palazzo of ca’ corner della regina blends seamlessly with Kounellis’ large scale installations that often feature everyday objects. Cabinets, hooks, classes of grappa, flowers, felt, and stainless steel planes are reinvigorated in order to blur the observer’s means of distinguishing between art and life. untitled (1993–2008), for example, uses the main room of the venue to force a re-examination of the everyday wardrobe, hanging them overhead as the viewer walks under.

The injection of the contemporary into a classical space has become a more and more omnipresent trope of curatorial practice today and can often go awry but Celant’s display truly hits the nail on the head when it comes to re-examining and indeed defining the legacy of one of the most important artists of the 20th Century.

Helen Frankenthaler @ Museo di Palazzo Grimani – Title: ‘Pittura/Panorama. Paintings by Helen Frankenthaler, 1952-1992’, Location: Castello, 4858A, Venice

Frankenthaler’s paintings were last shown in Venice in the 1966 Biennale when her work appeared with the US pavilion. Pittura/Panorama features 14 paintings that span 40 years and focus on the interplay between, well, painting and the notion of the panoramic. Large horizontal works, tending to be substantially wider than taller, take the onlooker into shallow but expansive spaces. The exhibition was organised by the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation and Venetian Heritage, in collaboration with Gagosian and coordinated by Gagosian’s senior curated, John Elderfield. It makes for a tranquil and introspective viewing experience and a welcome repose from the city’s often chaotic crush of tourists.

Lithuania – Title: ‘Sun & Sea (Marina)’ . Location: Magazzino n. 42, Marina Militare, Arsenale di Venezia, Fondamenta Case Nuove 2738/C (near Campo de la Celestia)

Any review of the Venice Biennale would be amiss without a mention of the Golden Lion winner, the Lithuanian Pavilion’s Sun & Sea (Marina). This operatic meditation on global warming was deeply moving and combined elements of performance, song-writing and installation to great effect.

Moving back to the Giardini/Arsenale… What else was new this year?

Ghana – Title: ‘Ghana Freedom’ . Location: Artiglierie of the Historic Arsenale

Despite the number of African countries to have national pavilions being down by one from 2017, this year marks the first time that Ghana and Madagascar have had pavilions at the Biennale.

Ghana’s pavilion in the Arsenale was designed by Ghanaian-British starchitect Sir David Adjaye working along-side curator Nana Oforiatta Ayim. Ayim brought six artists to the exhibition who cross gender, generational and geographic divides. She skillfully blended the work of those living and working in Ghana such as Ibrahim Mahama and installation artist Selasi Awusi Sosu with the Ghanian diaspora such as British-Ghanian filmmaker John Akomfrah and the London based painter Lynette Yiadom-Boakye.

Each section, which features newly commissioned works, has a certain grandeur and pride with a mix of historical referents specific to the country (such as those included in Akomfrah’s video called Four Nocturnes), found objects presented in a monumental format (El Anatsui’s massive and hard to classify works) and notions of blackness as shown through the figures of Yiadom-Boakye and Felicia Abban.

Canada – Title: ‘‘ISUMA’ , Location: Giardini

Another first is the premiere of Inuit art at the Biennale, brought to the Giardini by the Canadian Pavilion. The exhibit features a multi-panel video installation by the collective Isuma, led by Zacharias Kunuk and Norman Cohn and founded in 1990. Isuma is recognised as the first Inuit film production company. The fictionalised, multi-panel display gives visitors some inspiring insight into the underrepresented population while questioning their continued subjugation and displacement.

Meanwhile…

Technology takes centre stage…

A Biennale in 2019 wouldn’t be complete without the influence of technology making an appearance.

Showing at Norway’s pavilion is Norwegian-Nigerian artist Frida Orupabo who was discovered by American artist and filmmaker Arthur Jafa through Instagram. Orupabo focuses on themes such as race, sexuality, violence, identity and colonialism. Her work aims to challenge so-called ‘facts’ and show different ways of exploring and making sense of the world. With her nine-channel installation derived from her Instagramming found in the Norwegian pavilion, she is also the first to present work based on the social media platform at the Venice Biennale.

Another technological first could be found in Global Art Forum speaker Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s work, who presented the first ever virtual reality piece shown in the Venice Biennale’s central pavilion. The work is part of a project called Endodrome, a staged environment created to host five people at each time, combining an interactive VR experience with a theatrical setting. With a conference addressing art’s relationship with technological, social and environmental issues taking place in Venice in September, led by Rugoff and featuring artists such as Foerster and Tomas Saraceno, VR might be the start of a new Biennale trend.

So what can we make of all this?

Rugoff is characteristically known for his strong belief that ‘the most important thing that happens doesn’t happen inside the gallery’ but rather ‘what visitors do with that experience after they leave’. Perhaps Rugoff aimed to make visitors come away with more questions than answers, to force critical and independent thinking, to expand perspectives, examine what is meant by ‘truth’ and ‘fact’… We’ll let you be the judge.