Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child at the Hayward Gallery, London

Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child, on view at the Hayward Gallery until 15 May, is the first retrospective of the late artist that focuses on textiles and fabric. Although the title suggests links to Bourgeois’ childhood, the featured pieces were made in the last two decades before her death.

Bourgeois, the French-American artist who is most famous for her industrial-scale, bronze and steel sculptures of spiders, has explored the theme of abandonment repeatedly throughout her life’s work. She once said of the use of sewing in her pieces: “I always had the fear of being separated and abandoned. The sewing is my attempt to keep things together and make things whole.”

Bourgeois’ interest in cloth and embroidery that are prominent in this exhibit can be traced to her early childhood in her parents’ tapestry workshop in Paris. During her younger years, Bourgeois would work with her mother in restoring and repairing antique tapestries while her father would sell them.

Louise Bourgeois in 1990 with her marble sculpture Eye to Eye (1970s). Photo: Raimon Ramis. Estate of Louise Bourgeois /Wikipedia Commons.

The compositions in this exhibit are often, but never overtly, influenced by the series of traumas that Bourgeois dealt with throughout her life. Bourgeois has spoken openly about these psychological traumas, including her father’s string of affairs—especially a long-standing affair with Bourgeois’ governess—her mother’s illness and eventual death when Bourgeois was 22 years old, and her brother’s institutionalisation.

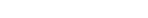

Throughout the show, much of Bourgeois’ pieces are composed of fabrics morphed into various body parts—heads, phalluses, torsos, breasts. Many of these works contain a tactile, worn-in, sometimes lumpy texture. Bourgeois especially used personal materials in her sculptures, such as the clothing of her mother and other family members as well as her own.

The ambiguous sculptures on display are rooted in specificity. In one work, a head made of pink cloth lies sideways with its ear cut off and its mouth open, as if screaming in agony. Pierre (1998) is titled after Bourgeois’ brother who suffered from mental illness and depicts Bourgeois’ guilt at their lack of communication.

In another piece, titled Lady in Waiting (2003), a doll-like figure sits in the middle of a chair of the same muted brown and beige fabric. Thin, steel spider-like legs protrude from the dolls stomach and strings emerge out of the doll and attach to the outer corners of the wooden and glass encasement the doll is inside of. The work evokes images of domesticity, perhaps of a woman’s life that she has not fully lived. The doll, which stands in for the woman, hides like an insect, camouflaging into the background. The tight enclosure surrounding the doll enhances the viewer’s sense of its claustrophobia.

In one of the last rooms, one of Bourgeois’ renowned spider sculptures is on view. Similar to Bourgeois’ other sculptures such as Maman (1999), Spider (1997) is a massive-scale work made of bronze and steel. A quote by Bourgeois on the wall of the exhibit reads, “I came from a family of repairers. The spider is a repairer. If you bash the web of a spider, she doesn’t get mad. She weaves and repairs it.”

This work is distinct in that it also contains a large steel cage beneath the spider. Within the cage are textiles, tapestries, and personal objects, such as bottles of Shalimar perfume which Bourgeois used. These items suggest themes of recollection and memory and root abstract imagery in the specificities of Bourgeois’ life.

The last room contains vitrines full of lumps of fabric that are suggestive of biomorphic forms. These sculptures that Bourgeois made during the last five years of her life are reminiscent of sagging body parts and are representative of Bourgeois’ own ageing. The emptiness and physical hollowness in some of the material is evocative of the loss that comes with that ageing.

The rooms within which Bourgeois’ pieces are displayed are large, spacious, and industrial. The concrete walls, harsh lighting, and gravity of the space in comparison to Bourgeois’ works, even her massive spiders, exacerbate sentiments of loneliness and abandonment.

Bourgeois used materials such as textiles and garments and presented them out of their usual context. Fabric that is ordinarily used to cover, clothe, protect, and decorate is morphed into unrecognisable forms and obscure figures. There is a consistent struggle always involved in her work. Needles act like spiders that both repair and injure, create and destroy, much like how Bourgeois saw her actions and the actions of others.

The exhibit not only describes the cathartic process of Bourgeois’ own artmaking but also the universality of pain and repair in these simultaneously comforting and distressing forms. Rather than seeking to find an end to the trauma that she endured, Bourgeois’ compositions embrace the process of healing as a recurring and continual encounter between pain and restoration.