The 60th Venice Biennale Foreigners Everywhere

Diverting from the fantastical Milk of Dreams two years prior, the 60th anniversary of the Venice Biennale, entitled Foreigners Everywhere, presented its audience with a headline that is provocatively rooted in both reality and conceptual play. Curated by Adriano Pedrosa who lifted the phrase from the Parisian collective Claire Fontaine, an ironic and imaginary persona who produces sardonic roving signage. Fontaine’s series of neons ‘Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere’ (2006), are scattered throughout the city, spelling out the Biennale’s title in a variety of languages varying on the venue.

For the international audience, the collection of these multiple disorienting markers visually personifies the discordant experience of the foreigner. Each pavilion navigates a glimpse into respective alienating interpretations, where the feeling of foreignness is spelt out and exacting, effectively activating each country’s own history and treatment of the outsider. The Latin word for stranger/foreigner has its etymological roots in extraneous or ‘from the outside’ and as one entered the hinterland of the Giurdini and Arsenale, both dislocated from the Venetian city, one questioned how far the concept of stranger could be reached. Artvisor takes a look at a selection of the pavilions this year.

Claire Fontaine Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere installation view at the Arsenale in Venice. Photo: Marco Zorzanello

Australia: Kith and Kin

Archie Moore’s (b.1970, Australia) kith and kin exhibition in the Australian Pavilion was awarded the Biennale’s Golden Lion for Best National Participation. The immersive show invites the viewer into a blackout room that centralises a table of documents. Erasure and heritage are explored through stacks of paper on the central table, displaying records of hundreds of Aboriginal deaths.

In 1991 the royal commission, an independent public inquiry reserved only for matters of exceptional public importance, decreed 339 recommendations designed to stop preventable deaths, since then 557 Aboriginal people died in police custody. Moore visualises this through the redacted coronial reports.

Surrounding the table is a watery pool below, turning the space into a reflective homage to the loss of life. By installing this feature, the artist enforces a distance between the viewer and records, Moore places impetus with a distanced perspective that grants an all-encompassing view of the historically disregarded lives of aboriginal peoples. Encircling the space is Moore’s own family tree written in chalk which provides a delicate juxtaposition between the ephemeral materiality, threatened with erasure through visitors touching it, set against the expansiveness and interconnectivity of Moore’s heritage.

Archie Moore Kith and Kin installation view at the Australian pavilion in Venice. Photo: Kitty Atherton

Greece: Xirómero/Dryland

Xirómero/Dryland is a collaborative pavilion by artists Kosas Chaikalis, Thanassis Deligiannis, Elia Kalogianni, Yorgos Kyvernitis, Yannis Michalopoulos and Fotos Sagonas, comprising of an interdisciplinary collection of installation, sound, video and lighting. The focal point of the show is the experience of a village festival, known as panigyria in mainland Greece, of which Thessaly and Xirómero are key cities where this tradition takes place.

The viewer is guided around this festival from the village square to the outskirts of the land which centralises on a piece of agricultural irrigation that rotates to these elements, releasing water in its process. The central object symbolises the materiality of rural Greece. What is represented is the dichotomy between the abundance of celebration and the scarce experience of agrarian labour.

This exhibition provides visitors with an immersive impression of walking into abandoned agricultural land with the distant recollection of a celebratory festival. The outsider’s dreams of the past and the harsh nature of reality coalesce. The question of the correlation between financial exhaustion, technological advancement and cultural activity are offset with the migratory experience of a desolate encounter.

Kosas Chaikalis, Thanassis Deligiannis, Elia Kalogianni, Yorgos Kyvernitis, Yannis Michalopoulos and Fotos Sagonas Xirómero/Dryland installation view at the Greek pavilion in Venice. Photo: Kitty Atherton

Poland: Repeat After Me II

Repeat After Me II is an audiovisual collaboration between the Ukrainian Open Group, a community of six young artists founded in Lviv, along with artists Yuriy Biley, Pavlo Kovach, Anton Varga. It provided an immersive show in which visitors were encouraged to repeatedly observe two pieces of footage from 2022 and 2024, in which civilian refugees interweave personal accounts of war with re-enactments of the sounds of weapons they remember. Despite the first video being shot in a camp for ‘domestic refugees’ outside Lviv, and the second series shot two years later outside Ukraine in a safer location, the sounds of war remain firmly entrenched in the participants’ collective trauma.

Despite the array of microphones on stands creating a stage in front of both pieces of footage, and indicating an invitation to mimic the noises, most visitors remained in the recesses of the seated area. This spoke to the commanding nature of the piece that made these interactions an impossible task.

Open Group, Repeat After Me (2022) installation view at Labirynt Gallery in Lublin, Poland. Photo: Bartosz Górka and Emilia Lipa

Serbia: Exposition Coloniale

Exposition Coloniale by Aleksander Denić (b, 1963, Serbia) explores the consequences of the colonial era. The pavilion is staged as a heterotopia, a Foucauldian transformation that creates an environment that is reminiscent of a city, and yet populated by ‘foreigners’ who enter this theatrical arena full of set-like installations.

The artist calls upon the visitors’ phenomenological receptors as much as the geo-political. Accompanied with the pavilion facade titled ‘Yugoslavia’, now dissolved after the conflicts of 1990, the sensory experience of navigating this space, equipped with music, sounds, lights and heating systems, allows the viewer to realise that Denić creates an ode to lost identity.

Denić presents the viewer with elements of consumerist life, a launderette, a meat counter, a photobooth, each instilling a sense of unease in the viewer as one meditates on its artificiality. Denić quotes sociologist Đuro Šušnjić in his press release, who meditates on the nature of history by noting there is both an ‘official history of memory’ and an ‘unofficial history of remembrance’. He expands by noting history exists in two states, it physically manifests itself through topographical adaptations and yet, these physical changes resonate emotionally in ‘the souls and spirits of the individuals’ as such ‘external history becomes internal…history becomes a biography’.

Aleksander Denić Exposition Coloniale installation view at the Serbian pavilion in Venice, Photo: Kitty Atherton

Great Britain: Listening All Night to the Rain

John Akomfrah RA’s (b. 1957, Ghana) Listening All Night to the Rain draws on the works of 11th century Chinese artist and writer Su Dongpo’s poetry. The artist explores the transitory nature of life along with continental relationships reflected in the experiences of diasporic people in Britain.

The exhibition brings together eight installations, from rural scenes, to rivers, conceived as a single landscape and arranged into ‘canto’s’, poetic movements that orient around the concept of time. The artist’s audial influences that accompany the footage draw on a variety of formative experiences, from club culture to protests in 1970-80s London, layering these sounds to create a sonic collage, and encouraging listening as a form of activism.

John Akomfrah Listening All Night to the Rain installation view at the British pavilion in Venice, Photo: Kitty Atherton

Malta: I Will Follow the Ship

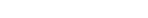

Matthew Attard’s I Will Follow the Ship, located at Arsenale, calls upon AI technology as a means of exploring cultural heritage. The artist’s interest in ex-voto ship graffiti, which can be found on the facades of chapels throughout Malta, are reimagined as with vernacular iconographies and local tales of seafarers who crafted such ephemeral graffiti because of the religious and political immunity of the religious locations.The ship remains a unifying metaphor for hope and survival historically, and contemporaneously in the crucial nature of the sea for survival.

Attard therefore bridges the historical stone drawings with new technologies. His contemporary digital drawing engages in digital eye-tracking, encouraging the audience to engage in the image production themselves, challenging the threat of technological singularity that AI often poses.

Matthew Attard I Will Follow the Ship installation view at the Maltese pavilion in Venice, Photo: Kitty Atherton

Saudi Arabia: Shifting Sands: A Battle Song

Manal AlDowayan’s Shifting Sands: A Battle Song brings together the sonic and geological features of the desert. Petal-like structures based on a crystal found in the desert in the artist’s hometown Dhahran, called ‘desert rose’, emanate from the ground in an organic manner similar to the position it was discovered in.

Striking against its natural structural influences, AlDowayan marks the forms with proclamations from Saudi women that challenge misconceptions and subsequently redefine their representation. As one circumnavigates the space, it reveals different messages printed on silk, the materiality and connotations of which act as an ode to the female form, its resilience and sensitivity. The installation follows the structure of Alardah and Aldahha battle ceremonies which are traditionally performed by men, subverting this convention to redefine images of womanhood.

Manal AlDowayan Shifting Sands: A Battle Song installation view at the Saudi Arabian pavilion in Venice, Photo: Kitty Atherton